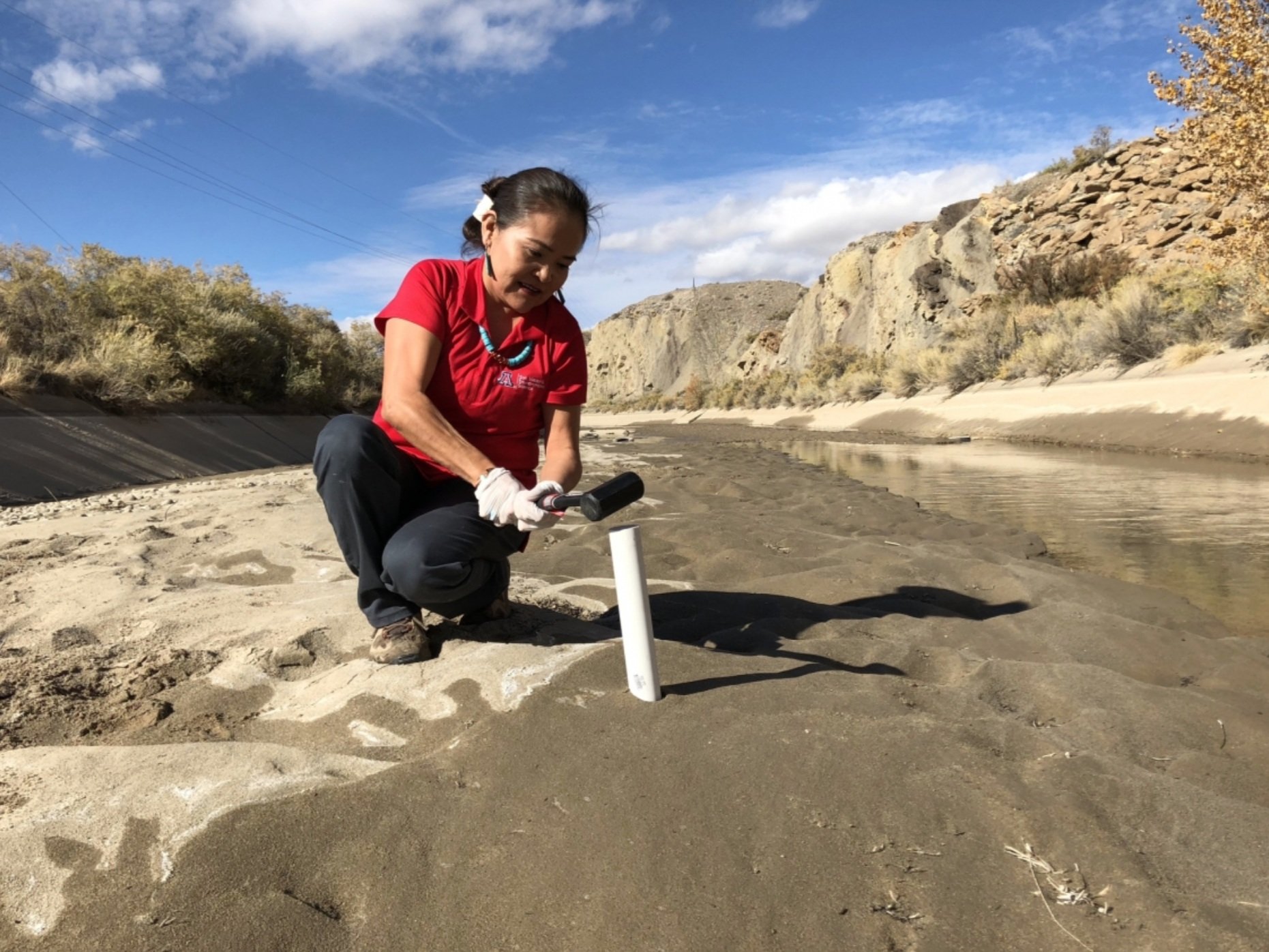

On October 19th, WINGS WorldQuest will induct five new Fellows during our 2022 Women of Discovery Awards Gala in New York City. In a special Q&A series, we are sharing a little bit about each honoree. Dr. Karletta Chief is a hydrologist working to improve our understanding, tools, and predictions of watershed hydrology, unsaturated flow in arid environments, and how natural and human disturbances affect soil hydrology, with an overall research focus on how Indigenous communities will be affected by climate change. Karletta is an associate professor and extension specialist in the Department of Environmental Science and current principal investigator for the Indigenous Food, Energy and Water Security and Sovereignty (Indige-FEWSS) program, an innovative collaboration between the University of Arizona and Diné College in the Navajo Nation, the oldest tribal college and university (TCU) partnership in the country. Karletta is pioneering engagement and partnership with Indigenous communities leading to transformative outcomes.

WINGS WORLDQUEST: Tell us your story. How did you get involved in science and your field specifically?

KARLETTA CHIEF: Let me formally introduce myself according to my Diné tradition. I am of the Bitterwater Clan and born for my father, who is of Near-the-Water Clan. My maternal grandfathers are of the Manygoats Clan and my paternal grandfathers are of the Red-Running-Into-the-Water Clan. This is how I identify myself as a Navajo woman. I am originally from Black Mesa, Arizona, but I currently reside in Tucson, where I am a Professor at the University of Arizona in the Department of Environmental Science.

I am a first-generation college graduate who was able to pursue higher education despite challenging circumstances because my parents encouraged me to learn and pursue education. My parents knew that the old ways of Navajo life were changing and, although they taught me ways of Navajo culture, they wanted me to be successful in a modern world. I was born and raised on the Navajo reservation and grew up in a home with no electricity, no running water, and little money, with Navajo as my first language. My parents’ teachings taught me to pray daily, work hard, appreciate life, respect others, and take pride in my culture.

Therefore, I believe that one can find a passion to fuel their determination to excel in life. My passion to succeed came from witnessing the environmental degradation in my hometown of Black Mesa. We lived so close to Peabody Coal that one day we were forced to move because my grandma’s corral caught on fire from the mine blasting. This background created a desire to go to college and use my education to help preserve and heal the environment and contribute to my family and people. No one in my family had ever attended college and few had the opportunity to attend school. My parents attended boarding school off the reservation, so they knew little about academics, much less college life. However, my parents believed in me and always told me that I could reach my dreams.

So as a high school student I knew education was important to achieve my goals and that I must study hard to succeed. I relied heavily on my school counselors for academic advice, because my parents could not provide this. My high school counselors were Amy Purdy and Jim Cliburn. In my freshmen year, they recruited me to be part of the Upward Bound (UB) Club. I found support and peer motivation with other Navajo students. This was the first time that I received academic mentorship where Ms. Purdy and Mr. Cliburn would ask about my academic work and college plans.

My family never left the reservation. We didn’t go on vacations, so my first UB Fall visit to the Southern Utah University campus was a big event. I remember riding the van over the mountain pass towards Cedar City watching the pinon and pine trees pass by. I was excited to visit a college campus and learn how to get into college. I immediately made lifelong friends during that trip and was motivated and inspired to excel in school. That summer Ms. Purdy invited me to attend the UB summer program. I remember telling my father of this opportunity. He was very suspicious of me interacting with people he didn’t know and how that would impact my growth and values. After Ms. Purdy offered to meet with my father and explain the benefits of UB, he eventually agreed to let me go for the summer. I then attended UB every summer of my high school career. I experienced college life while I was a high school student, and I believe this helped me adjust when I became a real college student. I took college classes, learned how to be in a study group, stayed in a dorm, and participated in extracurricular activities. The trips that we took to Las Vegas, Salt Lake City, and Los Angeles helped me to peer into city life and experience popular culture. Until then, I had never visited a city or gone to an opera or an amusement park. One of the most critical things that UB helped me with was studying for the ACTs for one week! Though they were long 6-8 hour days, I enjoyed working through the practice problems, studying, discussing test taking, and finally taking the exam. I believe it is through this rigorous test preparation that I was able to get a high score on the ACT.

When I was a high school senior at Page High School in 1994, I applied to NAU, ASU, and U of A. It didn’t really matter what college I attended. All I knew was that I wanted to simply GO to college. One day Mr. Cliburn sat me down and told me that my grades and test scores were high and that I should apply to Stanford University. I listened to his advice and applied. Up to that point in time, I had never even heard of Stanford University! I didn’t even know where it was! I temporarily forgot all about my application to Stanford and began making plans to attend the University of Arizona. One day, I went to the trading post at Gap to pick up our mail, and a letter from Stanford had arrived. I suddenly remembered my application and a thought of pure doubt of my acceptance flickered through my mind. But when I opened that letter, much to my surprise, it congratulated me on my acceptance, selected from a pool of 15,000 applicants to become part of a class of 1500. At that point, I realized the possibilities and realities of achieving dreams. I believe that UB had a critical role in making me competitive to be admitted to Stanford University, and for that I am forever grateful to UB.

My first year at Stanford was extremely difficult. It was a major cultural shock for me. No longer could I wake to the morning scents of coffee brewing and potatoes frying on the hot fire stove. For the first time, I had the luxury of electricity and a warm shower every morning. I felt like an alien who had landed on another planet. I almost dropped out of college my first quarter there. One of the hardest things was not being able to talk to my parents. They had no phone, and I was used to hearing their frequent words of wisdom, but for now I had to remember what they had taught me. Had I not had the initial immersion as a high school student at UB SUU, I think my adjustment at Stanford would have been even more challenging.

One of the main reasons I was able to complete my Stanford education was not only the UB preparation, but also because of my father’s constant encouragement and reminders that the strength of our ancestors was the strength that resided in me. He instilled in me the pride and confidence of knowing that I could achieve my goals. He said, “Our people have survived the Long Walk and today we continue to live upon our land. The strength of our people to survive the Long Walk remains in you because you are of the Bitterwater People. This strength gives you the ability to succeed.”

Whenever doubts of my ability to succeed began to pollute my mind, I would reflect on the teachings of my family. I would remember my people’s will to survive through the Long Walk. I would remember my parents’ boarding school experience and their struggle to learn English. I would remember my grandma talking about individual responsibility and the concept of “ááhóh ájítéego téiya bíigha.” It is important to remember where we came from and take the teachings of our people and their strength to help us attain higher education and accomplish our goals and dreams.

Our traditional elders also emphasize the importance of living a life in harmony and balance in your own body and with all the elements and life around you. Harmony means living a life of optimal health. I remember as a young child my parents would wake us before the dawn to teach us to prepare for the day and not to be lazy. The morning was marked with a daily run towards the east to greet the new day and to remove the cobwebs of laziness. Running to greet the new day built physical strength and helped one attain balance and harmony in their life. Even today, I fall back on the teachings of my parents when facing the stressors of life. I fall back on these cultural foundations that help me attain peace and harmony.

I describe my academic journey as a series of dark tunnels that are connected, and as I walked through these dark tunnels I would stub my toe along the way, forcing me to go in the direction I needed to go. My goal was simply to get a bachelor of science degree, and I never thought that I would go beyond that to graduate school. However, once I got to my senior year in college, my advisor encouraged me to apply to the master’s program. So I got my master’s degree in environmental engineering. I had a really good friend that I considered a mentor in the Native American community who always called me Dr. Chief, and he planted a seed in my mind with the thought of going for my PhD degree. I decided that if I was meant to get a PhD, then the resources would somehow become available for that to happen. As a master’s student nearing completion of the program, I applied for several different fellowships to pursue a doctorate degree. I was awarded (again to my surprise) a graduate fellowship from the National Science Foundation. This was a golden ticket to go to any university of my choice.

I realized that I was more interested in the natural physics of water movement as opposed to wastewater engineering. So I decided to make a switch and pursue a PhD in hydrology and water resources. I also desired to do my research with Native American communities. So I decided to go to the University of Arizona because I knew that they worked with tribes in research. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to do my PhD research focusing on tribal waters, but I did gain the tools I needed to be a hydrologist. I studied postfire hydrology for my PhD research. At the completion of my PhD program, I again was faced with options of where to go next. Since I wanted to keep open the option of an academic career, my advisor told me that I had to pursue a postdoc. So I decided to give it a try and accepted a postdoc position at the Desert Research Institute. As a postdoc, I worked on building a lysimeter, an underground container with soil that is instrumented with many different sensors so that we could understand the flows in and out of the soil both in vapor and liquid forms. It was there as a postdoc that I had the opportunity to do what I had always wanted, and that was to work with tribes on water research. My first project was with the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe in Nevada looking at the climate vulnerability of the tribe. This was the first project that involved very different disciplines, including social sciences, and it continued for over 10 years.

After completing my postdoc, I accepted an offer at the University of Arizona to be an extension faculty. I was very excited to be an extension of faculty, because I would have the opportunity to be a boundary spanner to Indigenous communities. I would be able to bridge the science from the university to tribal communities that centered on their water priorities. Since 2011, I have been working with tribes on the water challenges they face. This includes mining impacts, climate change drought planning, watershed hydrology, Indigenous knowledges and STEM education. I really love my job as an extension faculty. The opportunity to work with tribes is an honor, and to be mentored by Indigenous knowledge holders and to work with community leaders and grassroots organizations and tribal environmental managers is truly an honor. Through my work, I have attracted Native American students who want to work with me. They desire to do research with their communities and find that working with me could provide that opportunity.

As an extension faculty, I started a training program at the University of Arizona called Indigenous Food, Energy and Water Security and Sovereignty (Indige-FEWSS), which now has 38 graduate students. Our team is training them how to be leaders at the food-energy-water nexus and to understand how to work with Indigenous communities to co-design solutions to environmental challenges. The success of the Indige-FEWSS program opened a new opportunity to create a center that could sustain the training efforts, faculty engagement, tribal partners, and co-designing of environmental solutions. The Indigenous Resilience Center was launched in September of 2021, and we have hired staff and two new faculty to support it. We are working to find ways to sustain the elements of Indige-FEWSS. I am excited about this new endeavor and the opportunity to collaborate with my colleagues at the University of Arizona and continue to build and nurture partnerships with Native Nations to co-design solutions to environmental challenges.

It is with great honor that I accept the WINGS Women of Discovery Award and join my esteemed colleagues who have been recognized for their impactful research. I don’t do this work alone. Science with Indigenous communities occurs as a team effort with my community partners, faculty, staff and students who work alongside me. I also have a very supportive husband and family who make it possible to do my work. As a first-generation college student who became a professor by going through trial and error, I never imagined that I would one day receive such a distinguished award. My commitment to communities comes through my passion to give back to Indigenous communities and Diné communities. I represent my family and ancestors through my four clans as Bitterwater, Near-the-Water, Manygoats, and Red-Running-Into-the-Water Clans, and it is upon their shoulders and the Creator’s blessings to be able to be in this place to do the work I am doing but also remembering the challenges that Indigenous communities and peoples have come through and face today. I am incredibly grateful and humbled to receive this tremendous honor by WINGS.

WWQ: What is something you would like people to understand about your field and work?

KC: I am an extension specialist who aims to bridge the university with community through community-driven research in water research. I work to bring relevant water science to Native American communities in a culturally sensitive manner. My projects include The Indigenous Food, Energy and Water Security and Sovereignty Project, The Superfund Research Program Community Engagement Core, The Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe Climate Adaptation and Traditional Knowledge Project, Gold King Mine Spill Diné Exposure Project and the COVID-19 and Indigenous Resilience Project. Access to clean water is critical to the health of Indigenous peoples. Native Americans use water in many different ways that include water for drinking and house use, spiritual, culture, livestock and livelihood uses. In my work with the Superfund Research Program, we are addressing the challenge that Native American communities are disproportionately impacted by mining and have the highest rate of diabetes. The rate of diabetes increases when tribal members are exposed to arsenic-contaminated waters. Our goal is to engage Native American communities in community-based participatory research to develop and implement intervention and prevention strategies to decrease exposure to arsenic-laden waters and diabetes risks while providing training, education, capacity building, and engagement tools. We hypothesize that increased community engagement around Indigenous food sovereignty will promote healthy diets and active lifestyles that will reduce exposure to arsenic and diabetes risks.

I lead the NSF Indigenous Food, Energy, and Water Security and Sovereignty Training Program, and we are training 38 graduate students. Indige-FEWSS’s vision is to develop a diverse workforce with intercultural awareness and expertise in sustainable food, energy and water systems (FEWS), specifically through off-grid technologies to address the lack of safe water, energy and food security in Indigenous communities. I am also the director of the newly established Indigenous Resilience Center, which aims to facilitate efforts of UArizona climate/environment researchers, faculty, staff and students working with Native Nations to build resiliency to climate impacts and environmental challenges. As an extension faculty, I am able to work across departments to link environmental health disparities to my water research and community engagement.

The field of hydrology and water resources is broad and can be interdisciplinary. As a hydrologist, I position myself as an Indigenous environmental scientist who aims to be interdisciplinary, to identify research projects that are driven by Indigenous communities and that incorporate Indigenous knowledges with western science. In order for one to work with Native Nations, it is critical that they understand how to appropriately work with Native Nations. In my work, I advocate strongly for faculty, staff and students to be trained. This includes the development of learning modules and training on research ethics, Indigenous Data Sovereignty, cultural humility, tribal approval processes and Native American history and culture.

This is an unexpected and tremendous honor. I am indebted and thankful to WINGS for making a space for Women Scientists to be honored. I stand on the shoulders of all the women before me including Adzáá Tó’díchíínii, my great-great grandmother, who through her weaving survived the internment camp at Bosque Redondo during the Long Walk by weaving beautiful Navajo rugs and exchanging it for food. My grandmothers and my mom who gave my identity as Bitterwater Clan and taught me my Diné language and culture. I am inspired by Navajo leader Annie Wauneka, who was a public health activist in the 1970s and worked non-stop to help her people. I am inspired by her motto of “I’ll go and do more.” The women in my history and life, with the foundation of faith and prayer, have made my academic journey and my journey back to my people possible. Now as a professor, wife and mother, I strive to give back to future generations of women.

WWQ: What are the greatest barriers to more women working in science?

KC: The barriers I have faced as an Indigenous woman in science have varied and are likely unique from other women in science. I am a first-generation college student and, as a result, much of my journey has been through trial and error, often working alone to push boundaries so that I may be successful not only in my science but also in the long-term goal of ensuring the science benefits Indigenous communities around water.

For me, my biggest barrier has been finding mentors that understand where I come from and why I do what I do, and that understand that I do not have access to expertise in my family or in my community to build upon. A good mentor is someone that understands where I am coming from, has humility to help me and to train me; and to hold my hand and to guide me. I have had a lot of mentors who have not been good mentors to me because they did not understand my journey and where I was coming from, and as a result I have not always been efficient on my path toward being a scientist.

The second challenge is associated with microaggressions and insensitive comments regarding Native American culture and history. I have always had to speak up for and represent all Native Americans even though I only represent one tribe, because most of the time I am the only Native American in my classroom, in my research project or at a particular meeting. So as one of very few Native Americans in my field, I often carry the burden of educating others about what is appropriate and communicating basic education about Native Americans.

The third challenge, which is not necessarily a bad challenge but rather a commitment that I carry, is a commitment to my family, my obligations to my community, and my commitment to do research to benefit Native American communities. My deep connection to my home on the Navajo Nation continually brings me back personally to do my work and to simply be with my family and my community, and that may not always be understood by others.

The fourth challenge involves the responsibilities that I have as a mother while being a scientist. I am a mother of three children. One of my children has special needs and medical disabilities. So being a mother requires an important role to raise my children to know their Navajo language, culture, and history and simply just to be with them on a daily basis. I am responsible for taking care of my children, and I have a role as a mother to nurture them and be with them when they need me. This is often not understood as well. I see other male scientists who spend endless hours doing their work and research, but for me I am unable to give completely all of my time to science because I am a mother.

I can share one example of when I was a junior faculty with a newborn child. I often would have to step out of meetings to pump or breastfeed my newborn baby, and I didn’t feel supported as a new mother who was breastfeeding. Being the mother of a child who has special needs, I have faced challenges that are both mentally and physically exhausting to take care of a nonmobile, nonverbal child. As a woman in science I have experienced comments made to me about being a woman, a mother or an Indigenous person that are offensive. Early on as a junior faculty, I was afraid to stand up for myself or call those statements out. But now I recognize that it is important to speak up and say something even if it puts my work or job at risk. These are the four challenges that I believe I have faced and continue to face today as a woman in science.

WWQ: What gets you up in the morning?

KC: The beginning of a new day, the thought of new opportunities, learning, conversations, being with family, loving my job and loving life. Those are all things that I look forward to when I wake up in the morning.

WWQ: What’s your next challenge?

KC: My next challenge is developing the Indigenous Resilience Center and working to bring tribes, faculty and students together collaboratively to co-design environmental solutions with Native Nations and ensure that the science is meeting the priorities of tribal nations in a way that is decolonized, Indigenized and that centers tribal critical race theory.

WWQ: Describe yourself in three words.

KC: Dedicated. Passionate. Caring.